Global Data Locality – Why and How

Why

In folly, Facebook’s open source c++ library, you often see code like the following:

#define FOLLY_SETTING_DEFINE(_project, _name, _Type, _def, _desc) \

/* Fastpath optimization, see notes in FOLLY_SETTINGS_DEFINE_LOCAL_FUNC__. \

Aggregate all off these together in a single section for better TLB \

and cache locality. */ \

__attribute__ (( __section__ (".folly.settings.cache"))) \

std::atomic<folly::settings::detail::SettingCore<_Type>*> \

FOLLY_SETTINGS_CACHE__##_project##_##_name;

Let’s see what it means by

Aggregate all of these together in a single section for better TLB and cache locality.

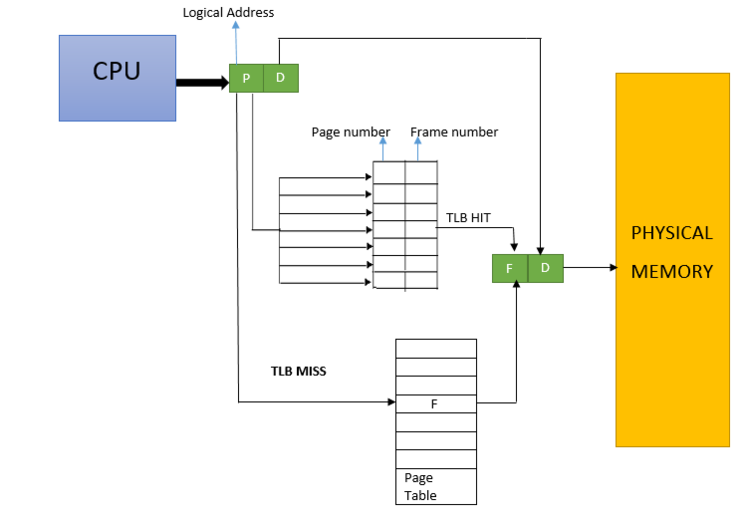

TLB stands for translation lookaside buffer. When CPU needs to load some value stored in RAM, it only has the address of virtual memory, which needs to be translated to physical address. Only then, the computer knows which subset of the physical 48 address lines (assuming x86-64 architecture), needs to be set to high voltage, and the remainings to low voltage.

Virtual memory is divided into pages. High order bits in the virtual address represent the page id. Low order bits represent the offset for the specific byte within the page. TLB is built in hardware which has limited storage. A typical TLB has 4Ki entries. Each entry in TLB is a mapping from page id to frame id of physical memory. For a given virtual address, if a TLB entry exists, it will find the frame id and get the physical address. All these steps are done in hardware. TLB is just a cache for page table which is stored in RAM, instead of dedicated hardware storage like TLB. On a TLB miss, CPU will walk the page table to fill TLB and restart the process. Page table is process specific, each process has its own page table in RAM. So there’s a special register CR3, that stores the address of the page table responsible for the current running process on the CPU. The CPU can do the page walk without OS’s involvement, which is why page table structure is architecture specific. Only when there’s a page fault, OS gets involved and can either swap in the data into RAM or halt the program. Notice TLB doesn’t have to be process specific. Usually on context switch, TLB gets flushed, so it only has lookup data for the current running process. But there are solutions like PCID in newer architectures.

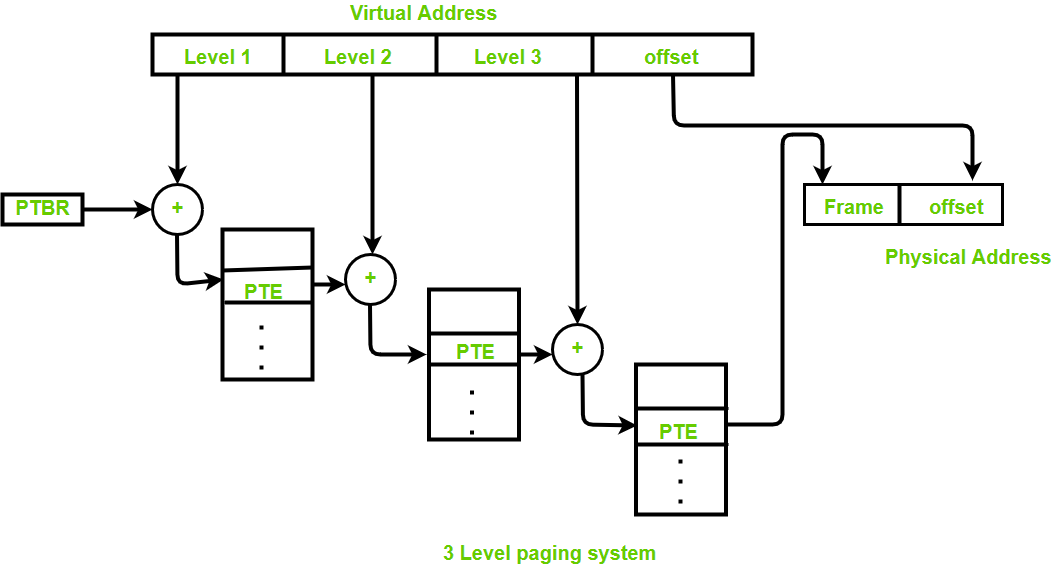

x86 has a two-level page table structure. The first part of the virtual address identifies the first level block (General Page Directory). The second part of the virtual address identifies the Internal Page Table Entry within the directory. Because page table lives in RAM, a page table lookup has all the overhead of accessing RAM. It requires two RAM access on x86, which requires an order of magnitude more CPU cycles, comparing to a TLB hit.

When CPU loads a e.g. uint64_t from RAM, it never just reads 8 bytes. The smallest chunk, a common CPU reads, would be 64 bytes a.k.a a CPU cache line. So the CPU would read 64 bytes starting from address that’s a multiple of 64, which contains the data you are interested in. This implies 1) you want to keep data frequently read together, physically closer together as well in virtual address space 2) you want to avoid data spanning across two cache lines if it can fit in one. That’s why you see e.g. ` attribute ((aligned (16))) being used for struct`s.

How

Now we know what TLB is. And why we want to to reduce TLB misses (because page table lookup is 10x slower) and increase cache locality. But how can we write program that has fewer TLB misses? For data in heap and stack, the normal good practices apply, e.g. avoid chasing pointers (a.k.a do not use linked list, align struct to avoid cache line misses). But how about global variables that are usually in .text and .bss sections.

__attribute__ (( __section__ (".folly.settings.cache")))

This is a gcc attribute for variables. So all variables with this attribute declared, will be created in the same section “.folly.settings.cache” in the final executable. So they would be physically closer in virtual address space once loaded in RAM.

I made tiny test program with the following line:

uint64_t __attribute__ (( __section__ (".test.mysection"))) section_data = 0;

objdump -D .section --demangle --section=.test.mysection -h

Sections:

Idx Name Size VMA LMA File off Algn

21 .test.mysection 00000008 00000000002b22e8 00000000002b22e8 000b22e8 2**3

CONTENTS, ALLOC, LOAD, DATA

Disassembly of section .test.mysection:

00000000002b22e8 <section_data>:

...

So the Linker creates a new section called “.test.mysection” and it’s exactly 8 bytes in size to hold the uint64_t, I defined, in the program. And when the program starts, the section gets copied to RAM.