Different ways of caching and maintaining cache consistency

Phil Karlton once said, “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.[1]“ There are other good variations of the quote. Mine personal favorite is Jeff Atwood’s quote, “There are two hard things in computer science: cache invalidation, naming things, and off-by-one errors.” Apparently caching is hard. Like almost everything in distributed system, it might not even look hard at first glance. I am going to go through a few common ways of caching in distributed systems, that should cover vast majority of cache systems you would use. Specifically I would focus on how to maintain cache consistency.

Cache & Cache consistency

Before we talk about different ways of caching, we need to be very precise about what we mean by cache and cache consistency, especially since consistency is a badly overloaded term.

Here we define cache as

a separate system, which stores a materialized partial view of the underlying data store.

Notice that this is a very general and relaxed definition. It includes, what normally you would think of as a cache, that stores same value as the (often durable) data store. It even includes something what people normally wouldn’t think of as a cache. For example, disaggregated secondary indexes of a database[2]. In our definition, it’s can also be a cache, and maintaining cache consistency is important.

Here we call a cache is consistent if

eventually the value of key

kshould be the same as the underlying data store, ifkexits in cache.

With this definition, a cache is always consistent if it stores nothing. But that’s just not interesting at all since it utterly useless.

Why use a cache

Usually cache is deployed for improving read/write performance. Performance here can be latency, throughput, resource utilization, etc. And usually these are correlated. Protecting database is usually also a very important motivation for building a cache. But you can argue that it’s also a performance problem that it’s solving.

Different kinds of cache

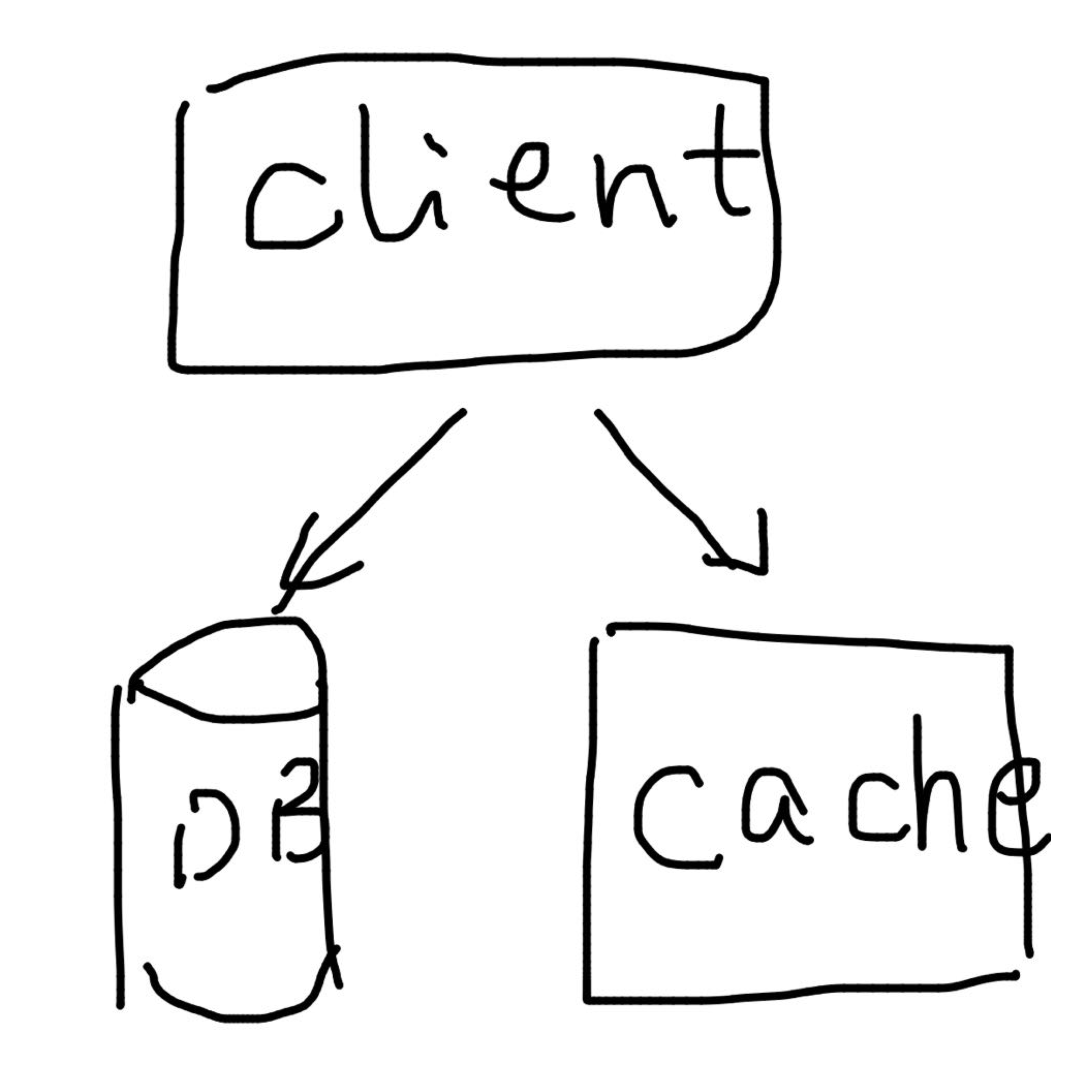

Look-aside / demand-fill cache

For look-aside cache, client will query cache first before querying the data store. If it’s a HIT, it will return the value in cache. If it’s a MISS, it will return the value from data store. That’s it. It says nothing about how the cache should be filled. It just specifies how it would be queried. But usually, it’s demand-fill. Demand-fill means in the case of MISS, client will not only uses the value from data store, but also puts that value into cache. Usually if you see a look-aside cache, it’s also a demand-fill cache. But it doesn’t have to be. E.g. you can have both cache and data store subscribe to the same log (e.g. Kafka) and materialize independently. This is a very reasonable setup. And the cache in this case is a look-aside cache but not demand-fill. And the cache can even have fresher data than the durable data store.

For look-aside cache, client will query cache first before querying the data store. If it’s a HIT, it will return the value in cache. If it’s a MISS, it will return the value from data store. That’s it. It says nothing about how the cache should be filled. It just specifies how it would be queried. But usually, it’s demand-fill. Demand-fill means in the case of MISS, client will not only uses the value from data store, but also puts that value into cache. Usually if you see a look-aside cache, it’s also a demand-fill cache. But it doesn’t have to be. E.g. you can have both cache and data store subscribe to the same log (e.g. Kafka) and materialize independently. This is a very reasonable setup. And the cache in this case is a look-aside cache but not demand-fill. And the cache can even have fresher data than the durable data store.

Simple, right? However simple Look-aside/demand-fill cache can have permanent inconsistency! This is often overlooked by people due to the simplicity of look-aside cache. Fundamentally because when client PUT some value into cache, the value can already be stale. Concretely for example

- client gets a MISS

- client reads DB get value `A`

- someone updates the DB to value `B` and invalidates the cache entry

- client puts value `A` into cache

Then from that point on, client will keep getting A from cache, instead of B, which is the latest value. Depends on your use case, this may or may not be OK. It also depends on if cache entry has TTL on it. But you should be aware of this before using a look-aside/demand-fill cache.

This problem can be solved. Memcache e.g. uses lease to solve the problem. Because fundamentally, client is doing read-modify-write on cache with no primitives to guarantee the safety of the operation. In this setting, the read is read from cache. modify is read from db. write is write back to cache. A simple solution for doing read-modify-write is to keep some kind of “ticket” to represent the state of the cache on read and compare the “ticket” on write. This is effectively how Memcache solves the problem. And Memcache calls it lease, which you can of as just simple counter which gets bumped on every cache mutation. So on read, it gets back a lease from Memcache host, and on write client passes the lease along. Memcache will fail the write if lease has been changed on the host. Now get back to our previous example:

- client gets a MISS with lease `L0`

- client reads DB get value `A`

- someone updates the DB to value `B` and invalidates the cache entry, which sets lease to `L1`

- client puts value `A` into cache and fails due to lease mismatch

Things are consistent again :)

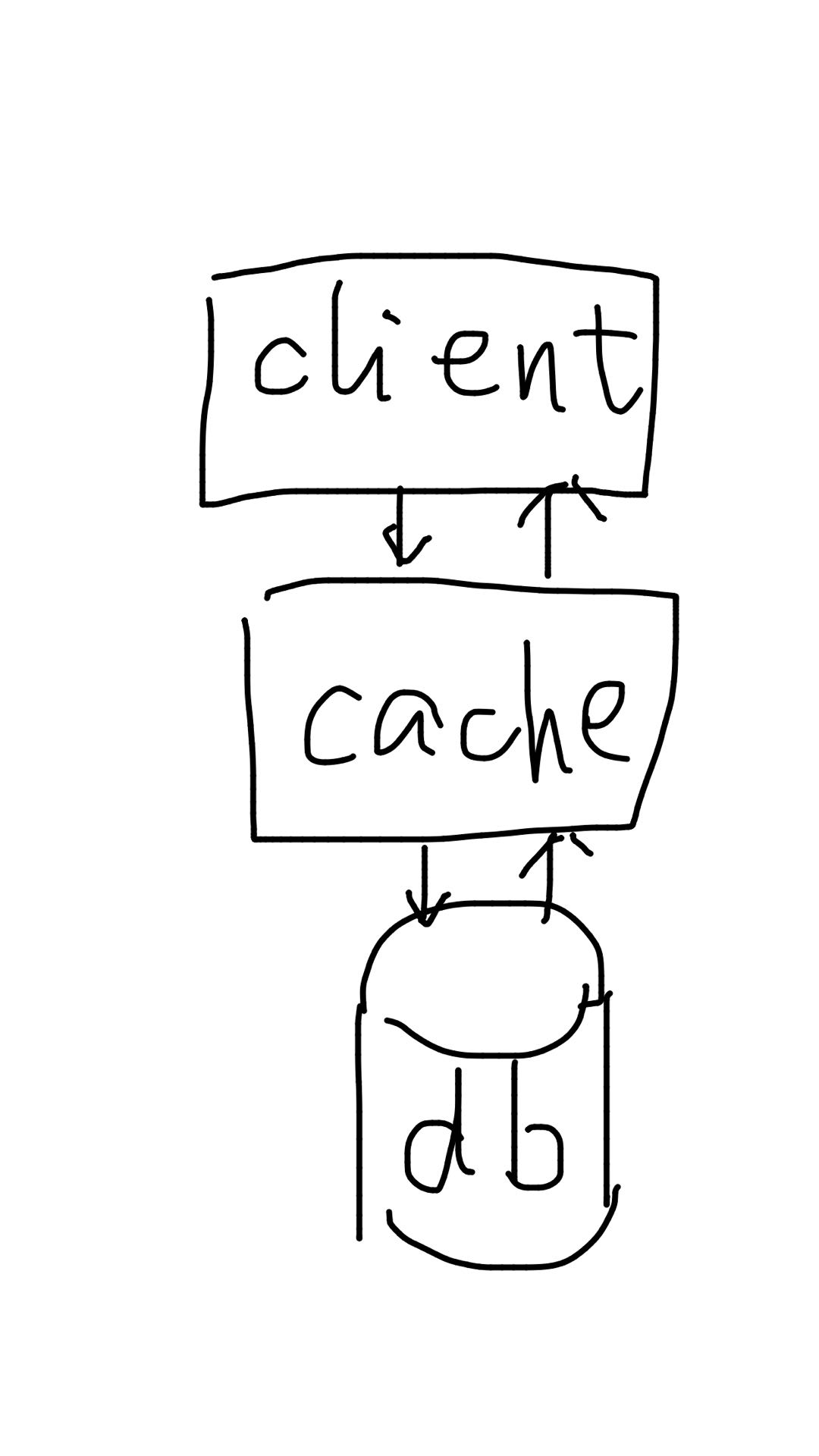

Write-through / read-through cache

Write-through cache means for mutation, client writes to cache directly. And cache is responsible of synchronously write to the data store. It doesn’t say anything about reads. Clients can do look-aside reads or read-through.

Write-through cache means for mutation, client writes to cache directly. And cache is responsible of synchronously write to the data store. It doesn’t say anything about reads. Clients can do look-aside reads or read-through.

Read-through cache means for reads, client reads directly from cache. And if it’s a MISS, cache is responsible of filling the data from data store and reply to client’s query. It doesn’t say anything about writes. Clients can do demand-fill writes to cache or write-through.

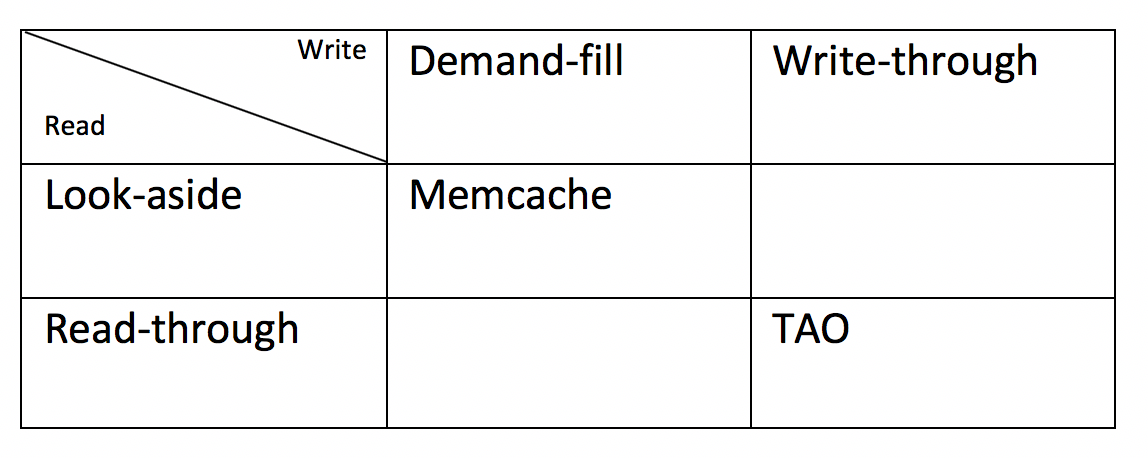

Now you get a table looks like

TAO (TAO: Facebook’s Distributed Data Store for the Social Graph) for example is a read-through & write-through cache.

TAO (TAO: Facebook’s Distributed Data Store for the Social Graph) for example is a read-through & write-through cache.

It’s not very common to have write-through & look-aside cache. Since if you have already built a service that sits in the middle of client and data store, knows how to talk to the data store, why not do it for both read and write operations. That being said, with limited cache size, a write-through & look-aside cache might be the best thing for hit ratio depending on your query pattern. E.g. if most reads would follow immediately after the write, then a write-through & look-aside cache might provide the best hit ratio. Read-through & demand-fill doesn’t make sense.

Now let’s take a look at the consistency aspect of write-through & read-through cache. For single box problem, as long as update-lock for write and fill-lock for read are grabbed properly, read and writes to the same key can be serialized and it’s not hard to see that cache consistency will be maintained. If there are many replicas of cache, it becomes a distributed system problem, which a few potential solutions might exist. The most straightforward solution to keep multiple replicas of cache consistent is to have a log of mutations/events and update cache based on that log. This log serves the purpose of single point of serialization. It can be Kafka or even MySQL binlog. As long as mutations are globally total ordered in a way that’s easy to replay these events, eventual cache consistency can be maintained. Notice that the reasoning behind this is the same as synchronization in distributed system.

Write-back / memory-only cache

There’s another class of cache that suffers from data loss. E.g. Write-back cache will acknowledge the write before writing to durable data store, which obviously can suffer from data loss if it crashes in between. This type of cache has its own set of use cases usually for very high volume of throughput and qps. But doesn’t necessarily care too much about durability and consistency. Redis with persistence turned off fits into this category.

-

According to https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TwoHardThings.html and https://skeptics.stackexchange.com/questions/19836/has-phil-karlton-ever-said-there-are-only-two-hard-things-in-computer-science, this famous quote indeed came from Phil Karlton. ↩︎

-

It doesn't work like regular aggregated secondary indexes, as if you read from the index, it might be lagging and show stale results. Normal ACID attributes of relational database doesn't specifically mention indexes. I would say database with disaggregated secondary index, breaks atomicity in ACID. ↩︎