DNS – the first distributed database

DNS was created in 1983. Before then, Stanford was storing the host name to IP address map on HOSTS.TXT, which obviously doesn’t scale. DNS is the address book of the internet, which performs a simple function of translating domains to IP addresses. One way of looking at it is that it’s a distributed read-heavy database with caches on top. Just like the internet is probably the first distributed system at large, DNS is probably the first distributed database ever - if you think about DNS as a whole that stores this lookup map and serves reads & writes operations to this map.

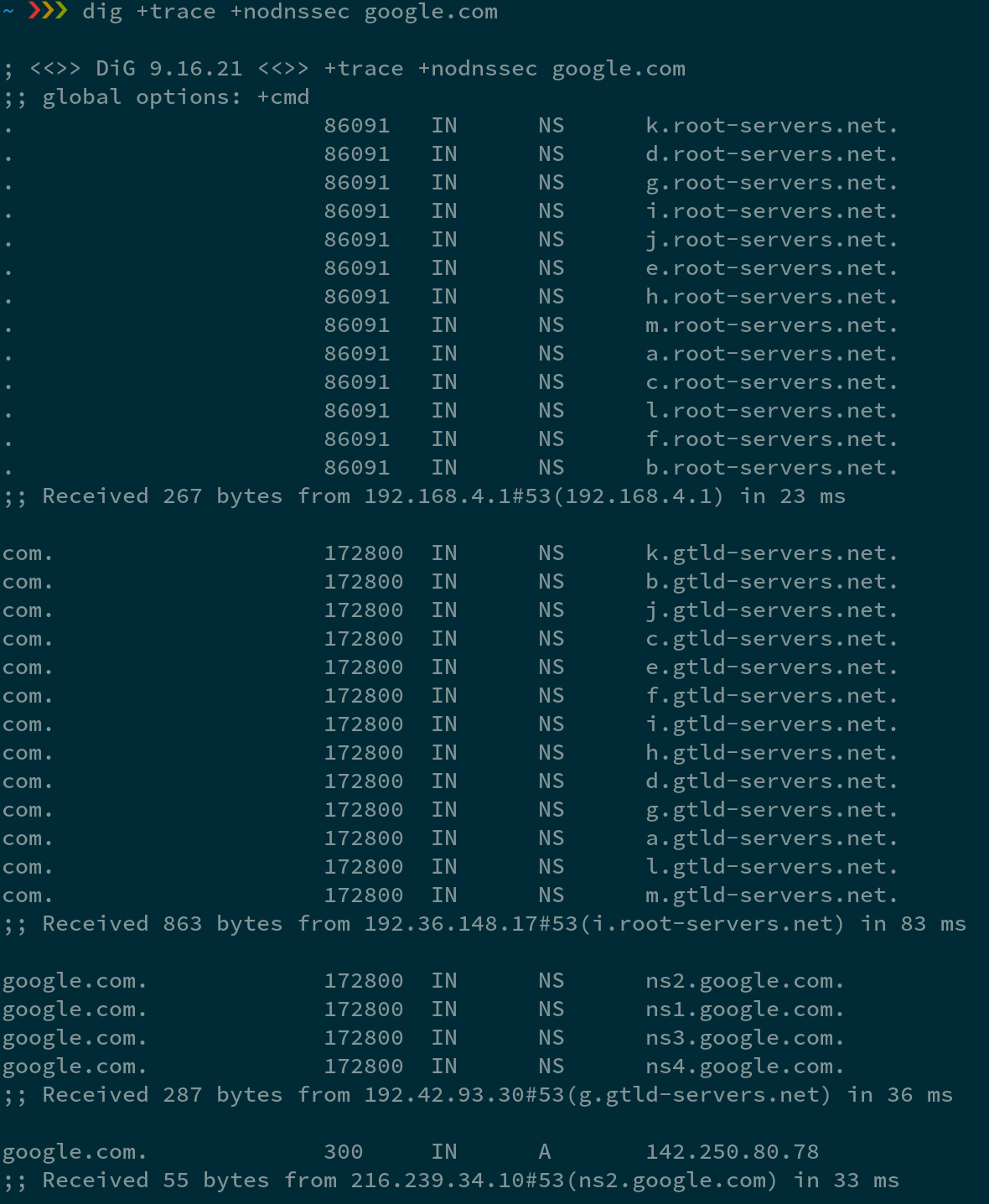

Let’s try a query

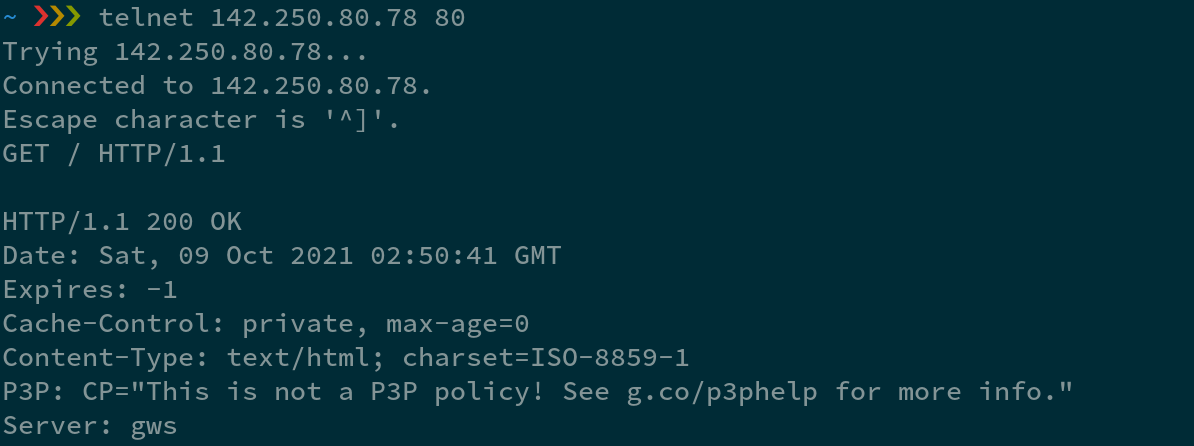

Given google.com, it returned me an IP address 142.250.80.78. From the trace, you can see, it first hit 192.168.4.1 at port 53, which is the IP address of my home router and the DNS port (in this case it has the result cached). It got back the thirteen root name servers - [a-m].root-servers.net. Thanks to anycast, there are way more than just 13 physical root name servers. As you can see, it picked i.root-servers.net(192.36.148.17) to ask “where can I find someone who knows about .com top level domain names”. It then got back another 13 global TLD (top level domain) servers - [a-m].gtld-servers.net. Next, it picked g.gtld-servers.net to ask about google.com, who replied with ns2.google.com. Finally, it asked ns2.google.com, who replied with 142.250.80.78. Notice that even though dig lists replies with human readable domains of name servers, DNS is itself must receive IP addresses. Otherwise, it would just create a circular dependency for no reason. Now we have one IP address for google.com, let’s try it out.

telnet returned me google.com’s HTML content.

Read path

What we just walked through is effectively the read path of the DNS-database. As a distributed database, where is google.com=142.250.80.78 stored? What we saw above is that the data is only stored on google’s name servers (we got it from ns2.google.com). Google obviously has a lot of name servers, and is technically a distributed system by itself. But if I have a much smaller website with much less traffic, a single name server will do (and even that server is certainly shared with other domains). If that single name server goes down, people won’t be able to resolve its domain name (at least after all the previous cached results expired). But Google’s name server cluster is much more resilient to failures, and can handle much more traffic. This is actually fairly interesting. Most distributed databases suffer from hot spots, when a few keys are accessed heavily. DNS-database handles such hot spot issue by allowing increasing replication factor at a per-key (name server) level. Purely from a scalability perspective, if a key is rarely accessed, you only need one replica. On the other hand, if a key is heavily accessed, you can create as many replicas as you want, and scale up the reads.

Another type of data stored, in the DNS-database, is the “topology” itself (or the who-owns what-map) e.g. “ns2.google.com knows about google.com”. This information (data) is also replicated, and cached in many of the physical TLD servers.

So the key of our DNS-database itself is hierarchical - e.g. /com/example/blog. Does it remind you of Zookeeper’s API? Replace / with ., and reverse the order, you get blog.example.com.

Write path

What happens if I want to store “key=value” (e.g. “example.com=x.x.x.x”) on DNS? First of all, the data needs to be stored in my own name server(s) with its own IP y.y.y.y, let’s say. Now we need to let others know “y.y.y.y knows about how to translate example.com to IP address(es)”. The information that y.y.y.y knows about example.com itself is also data, which gets propagated via BGP, which basically gossips the information to neighbour ASes. The number of ASes in the world is fairly limited. So the process of data discovery is like asking in the classroom if someone knows the name of a newly transferred student. The newcomer will tell his/her neighbours about his/her name - BGP announcement. Each student’s memory is effectively a routing table. By propagation, anyone (AS) in the classroom can find out who knows the newcomer’s name.

In database term, this process is called data discovery. Instead of being stored in a routing table, the data is usually stored in a shard-map. But the concept is the same - storing information about who-knows-what. For a distributed database, a shard-map is usually stored in a small highly reliably and available metadata store (e.g. ZooKeeper). There’s usually only one entity can modify the shardmap (e.g. DBA, or some automation). But that’s not the case for our DNS-database. Anyone can make BGP announcement. It’s like everyone in the classroom can claim to be the new student and knows his/her name. It’s a real problem called BGP hijacking. Authentication is the answer - basically in our analogy, I will only trust your announcement, if you show me your student id with your name on it. Hence, our DNS-database is still a single leader system, although the leadership is at a per-key granularity.

What if we need to update the data? The analogy would be what if a student wants to change his/her name? His/her name is effectively cached in most students’ brains. It’s hard to perform push invalidation at scale correctly, as it would require at-least-once delivery to everyone that might have the old data cached. Putting a TTL on the cached data, on the other hand, scales fairly well. However, it’s not without compromises. It means a DNS change would take at least minutes to propagate throughout the internet - eventual consistency.

There’s nothing new under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

Eventual Consistency, dynamic replica - they can be found in a protocol that’s more than 30 years old. They are not new.