Understanding Paxos as a Read-modify-write Transaction

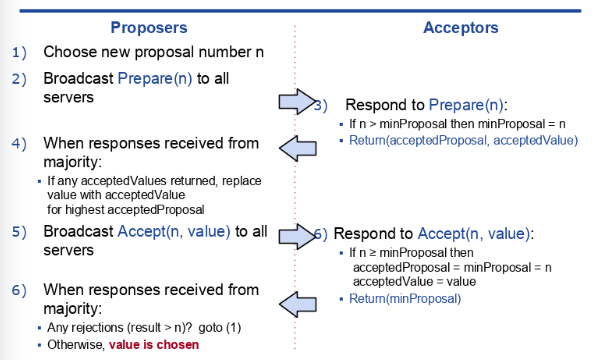

Paxos in one hand is very concise. It fits in a single slide.

On the other hand, Paxos is notoriously hard to apprehend. In this post, I will explain Paxos as a read-modify-write transaction, which is much more intuitive in my opinion.

TL;DR

Paxos is essentially a read-modify-write transaction. It’s as simple as:

- Read from the majority of Acceptors to find out if a value is already chosen and which value is it.

- Modify the proposal to the potential chosen value.

- Write/propose the value to Acceptors.

Ballot number (a.k.a proposal id), is used to resolve the read-modify-write race when there are multiple Proposers.

Preliminaries

Ordering https://blog.the-pans.com/time-and-order/

Distributed system is all about ordering. “Time” to a computer, is just a sequence of ordered events. Computer speaks the language of events. On the other hand, “Time” is a more intuitive concept to us than logical clock (a.k.a version). To help us apprehend a distributed system, we can treat a totally ordered sequence of events as the time axis in our distributed system universe.

Read-modify-write https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Read–modify–write

Read-modify-write is a typical atomic operation, which you can spot in CPU, Database, etc. E.g. there are two threads both trying to increment an int variable by one. A naive solution would have CPU instructions like:

- read the memory and store the value in a register

- increment the value and store the result to the register

- write the value to memory

The bug here is that both threads can read the value e.g. 4 in step(1) both bump the value to 5, and then write to RAM. This is wrong as we are expecting the end result to be 6.

There’re various ways of implementing read-modify-write transactions. E.g. you can take an exclusive lock like in 2pc, or you can take a lease on read and fail the write operation if a race is detected. Memcached uses lease to implement CAS (a.k.a Compare-and-set), which is just a synonym for read-modify-write.

Consensus https://blog.the-pans.com/paxos-explained/

The goal of Paxos is to achieve consensus (agreeing on a single chosen value) among 2F+1 hosts, that can tolerate at most F failures. The only failure modes we are dealing with are crash-stop and long message latency or packet loss. The requirement for the algorithm is to achieve both Liveness and Safety.

Liveness - some value will eventually be chosen as long as majority of the hosts are available.

Safety - one and only one value can be chosen.

Terminology

- Proposer: someone who proposes values

- Acceptor: someone who accepts values

A value is considered chosen, if and only if when it’s accepted by the majority of Acceptors.

Let’s dive in!

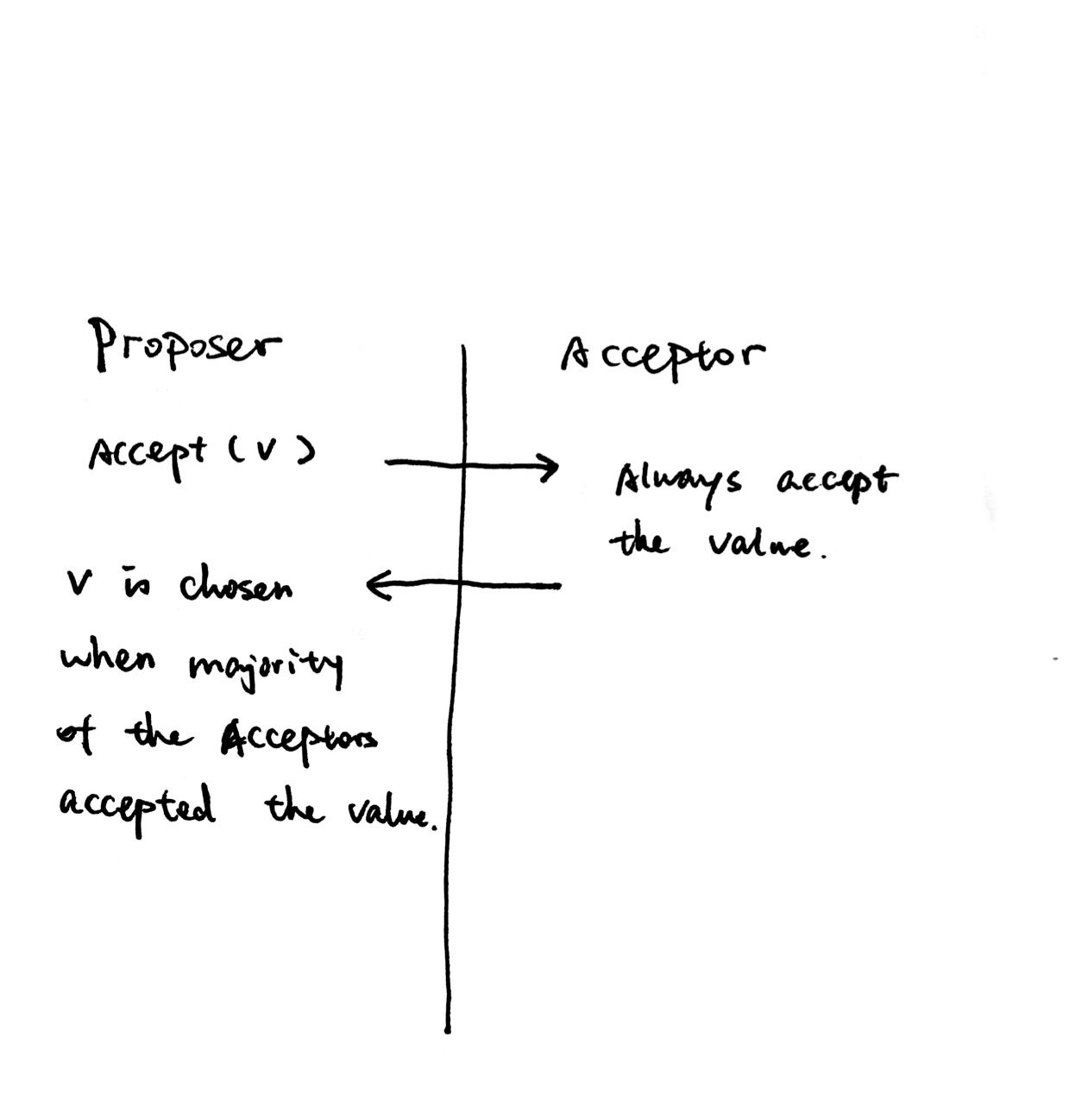

Consensus with a single Proposer

If there’s only one Proposer, achieving consensus is simple!

Another name for this single Proposer is the Leader. Most implementations of Multi-Paxos has the concept of Leader, who’s the only one sending out proposals. The benefit of a stable leader is that you only need one round-trip to get consensus.

The elephant in the room is that what if the leader crashed? Then we have to perform leader election, which itself is a consensus problem! What if we work-around the leader election problem by relying on a “hard-coded” consensus?

Terms (add ordering)

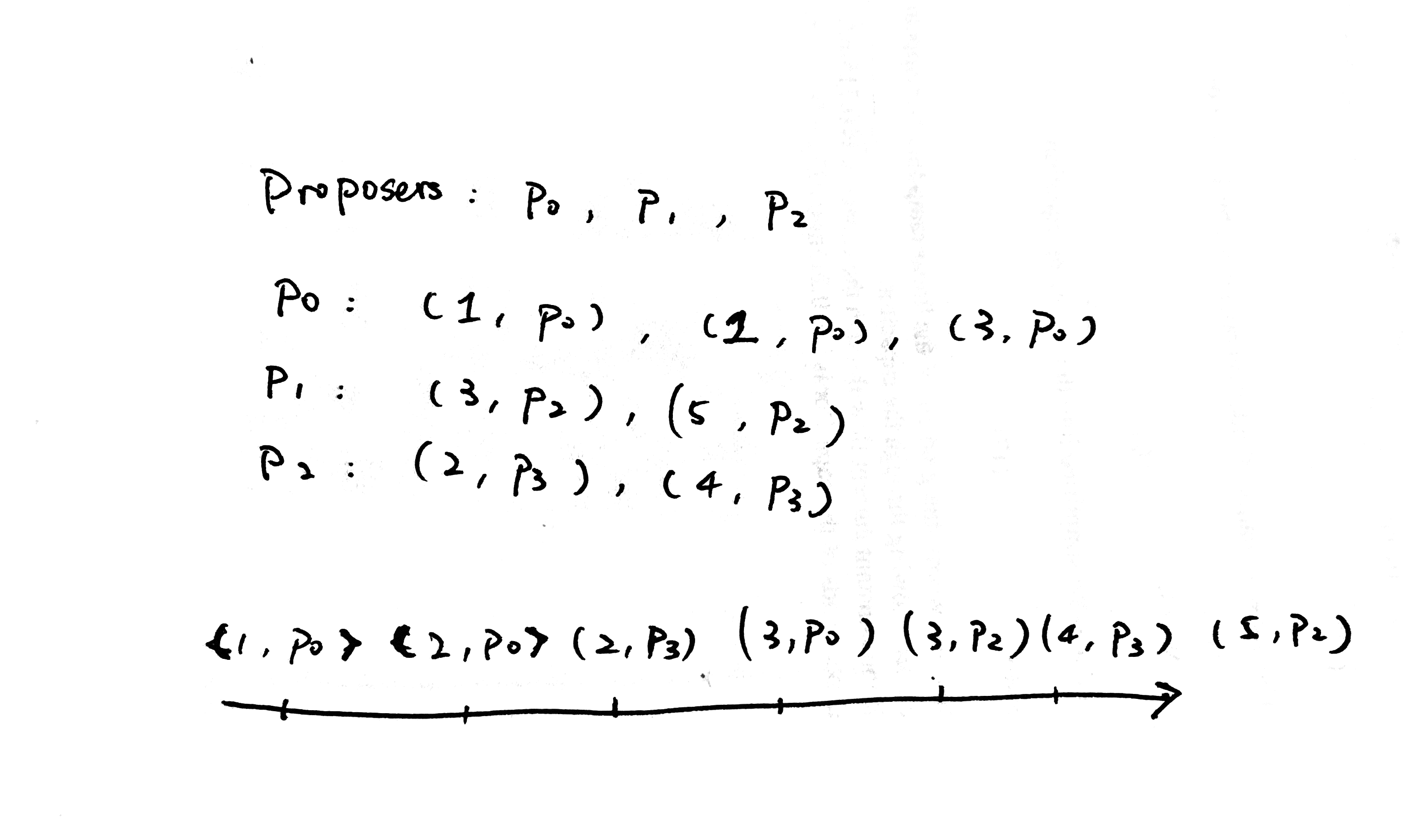

Remember ordering is our friend in distributed system. We can order “leadership” a.k.a terms.

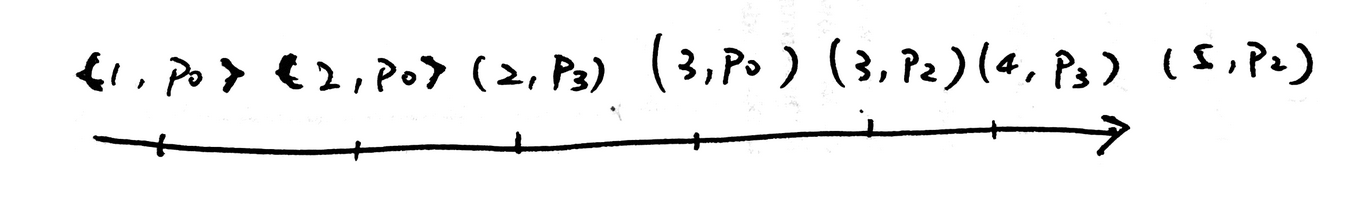

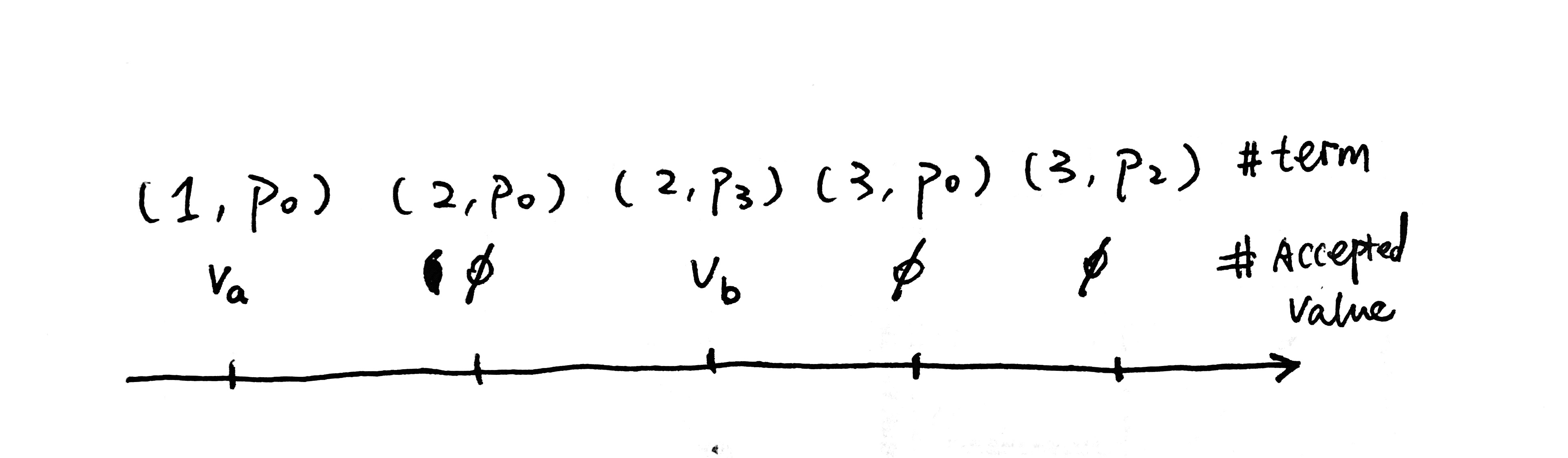

Let’s say we have three Proposers, p0, p1 and p2. Their own proposals are totally ordered locally, e.g. (1, p0) -> (2, p0) -> (3,p0). If we impose a “hard-coded” ordering between Proposers, p0 < p1 < p2, we get a total ordering of all proposals.

This is the clock of our system. Instead of thinking of them as proposals, we can treat them as terms of leadership, i.e., between time [(2, p3), (3, p0)), p3 is the leader for term (2, p3). Now we have sort of worked around the leader election problem by introducing the concept of term. Whenever a Proposer proposes with a term number (a.k.a Ballot number in the original Paxos paper), it is the leader for that term.

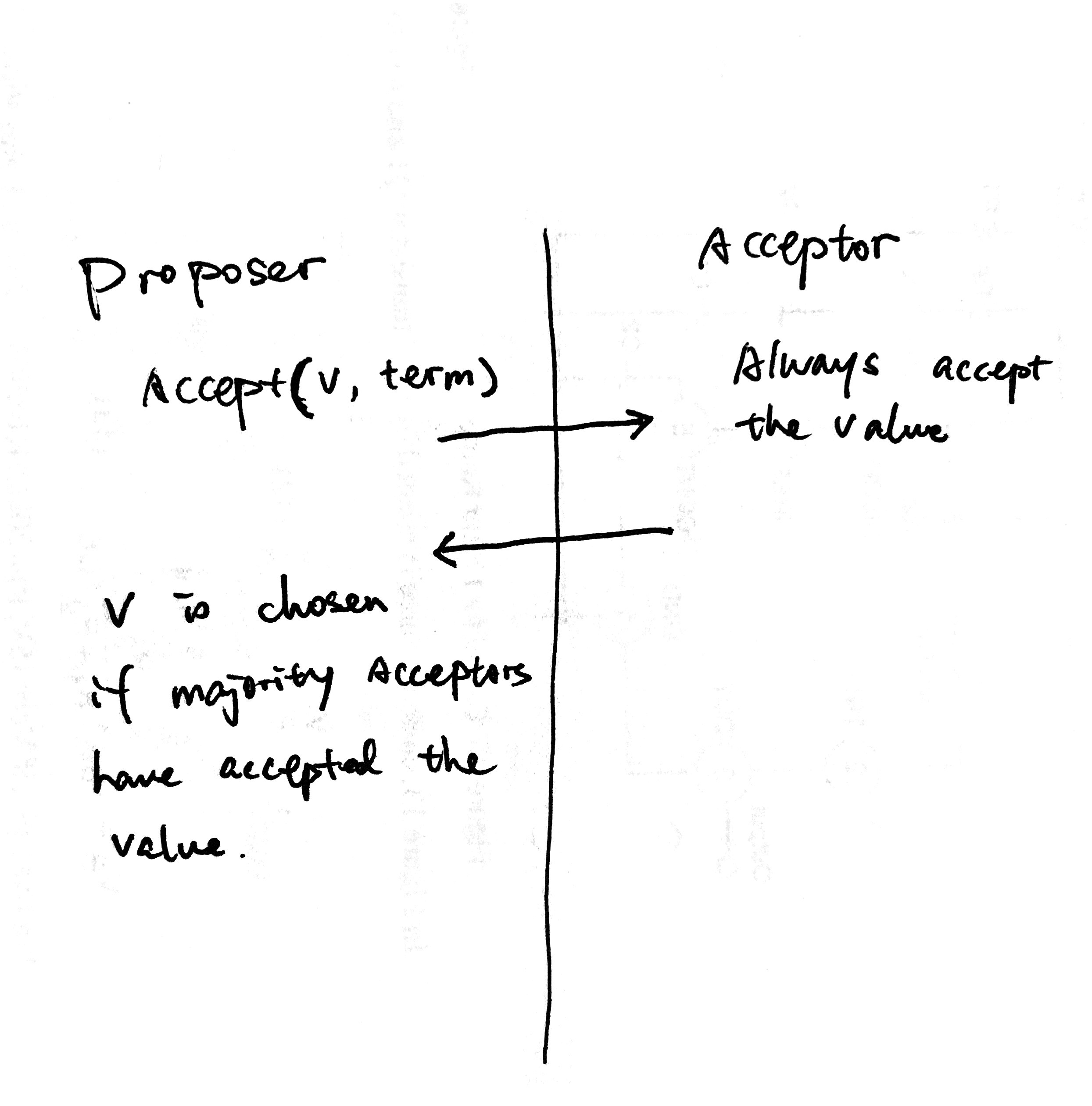

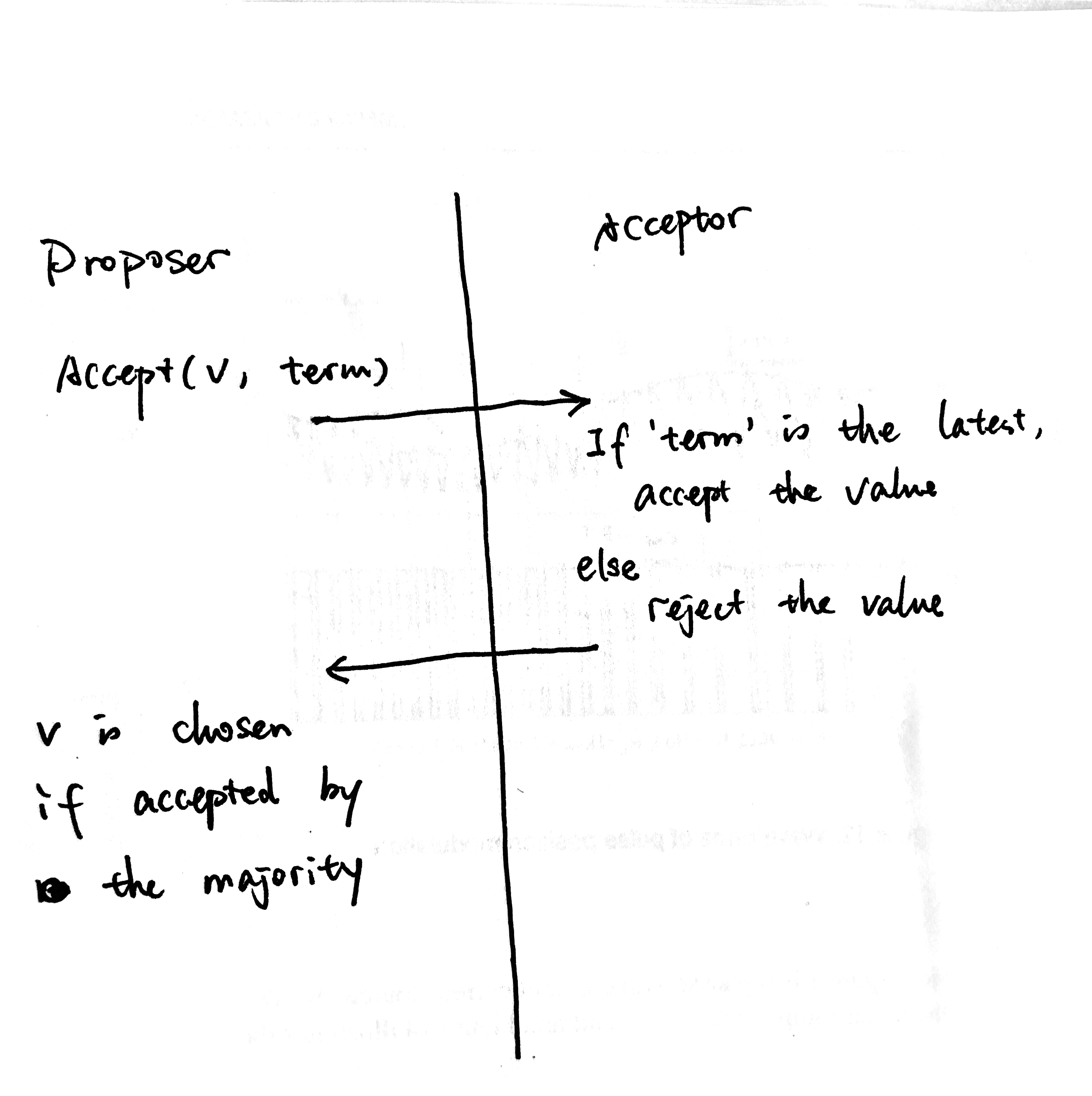

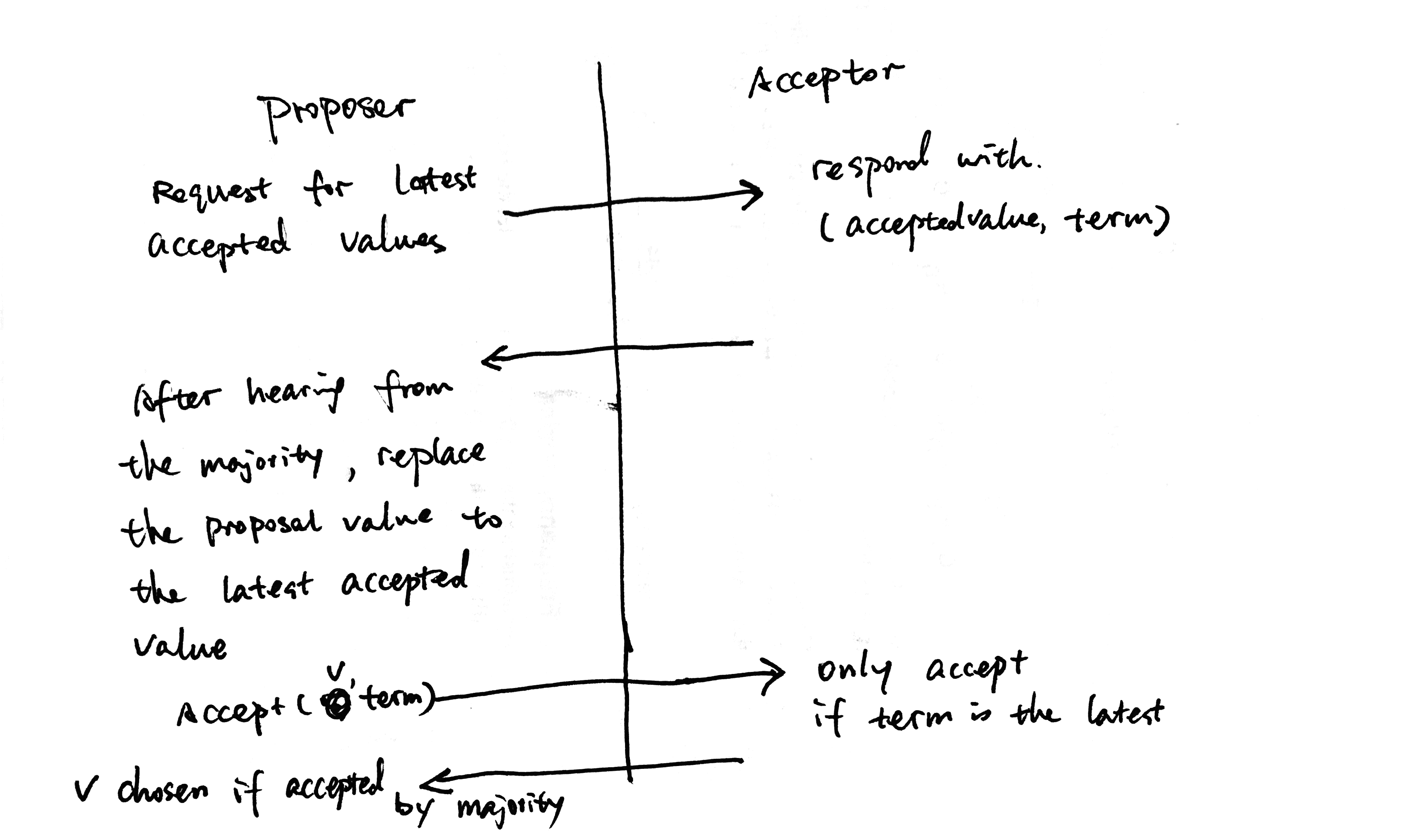

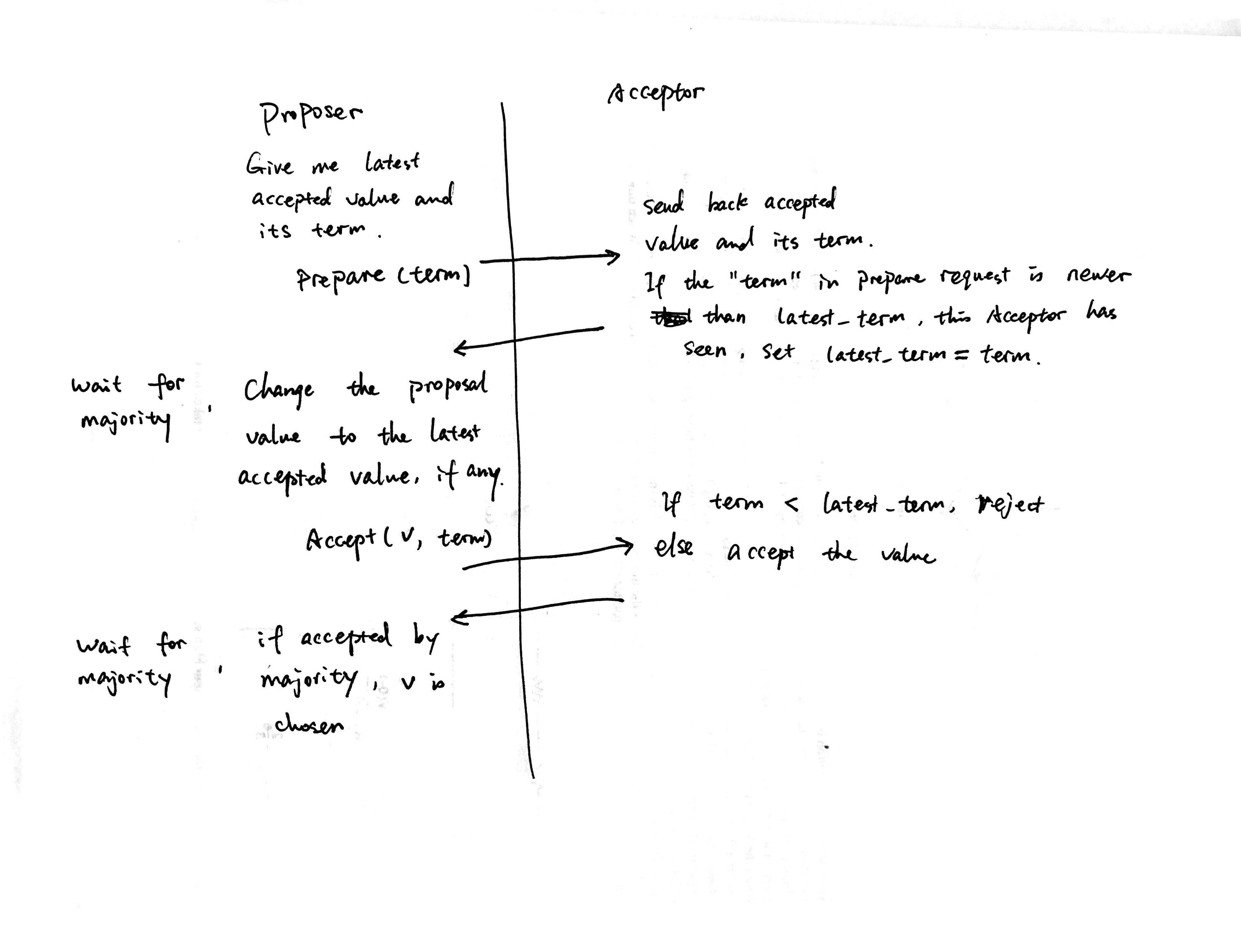

Now the algorithm looks like:

The only difference between this and the single Proposer is that we added term in the Accept request. We need to relax the single Proposer restriction. But this obviously doesn’t work for more than one Proposers, as the second Proposer can overwrite the chosen value proposed by the first Proposer, which violates the Safety requirement.

Reject proposals from previous Leaders (detect race)

We added term, but haven’t used it yet. Acceptor can use the information to have a local view of leadership over time.

Invariant(1): The Acceptor should only accept value from the latest leader.

If this Acceptor gets an Accept request for term (4, p3), it can simply reject it because p3 is no longer the latest leader. p2 is.

This algorithm still suffers from the problem that a newer leader can overwrite a previously chosen value.

Read-modify-write

The Proposer should read about the potential chosen value before sending Accept request to Acceptors.

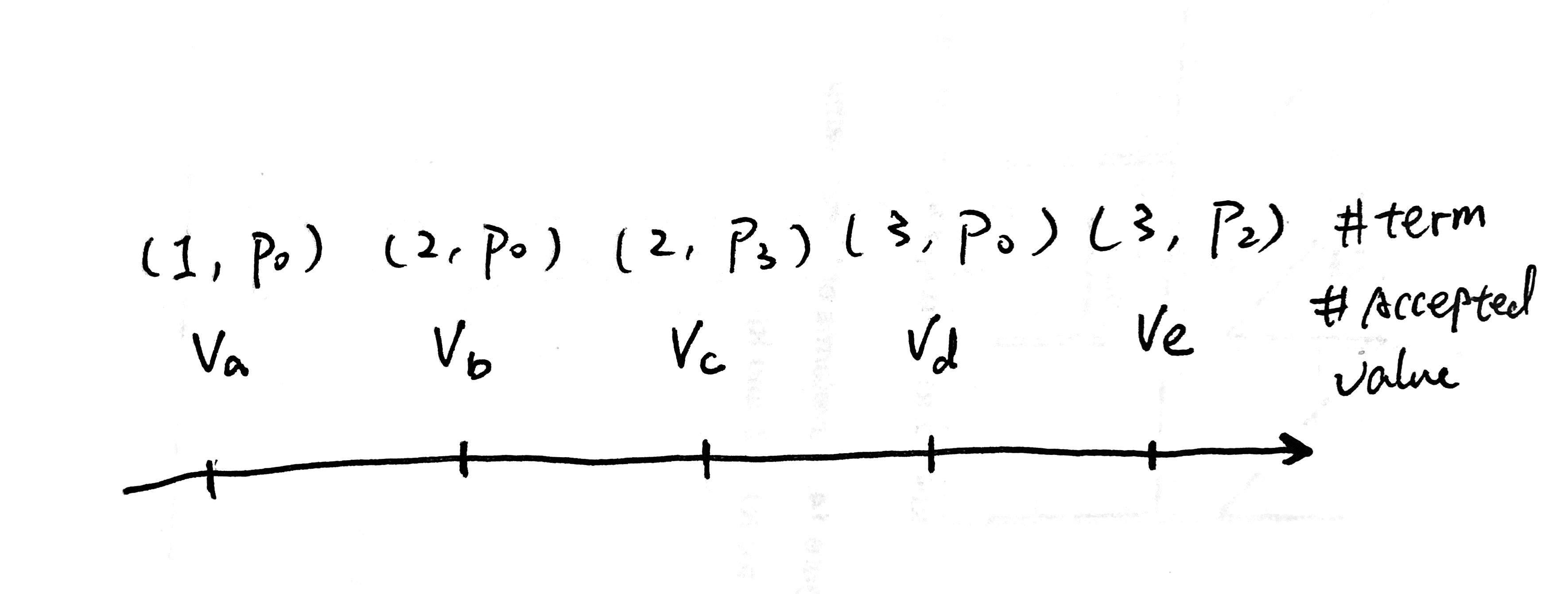

Now each Acceptor has a local view of leadership over time that looks like:

Based on our current algorithm, for each term there’s a value associated with it.

We want to make sure that if a value is already chosen, the Proposer should change its proposal to be the same value. This is exactly Read-modify-write.

- Read potential chosen value from Acceptors.

- Modify the proposal to be the same value of the potential chosen value.

- Write/Propose the value to Acceptors.

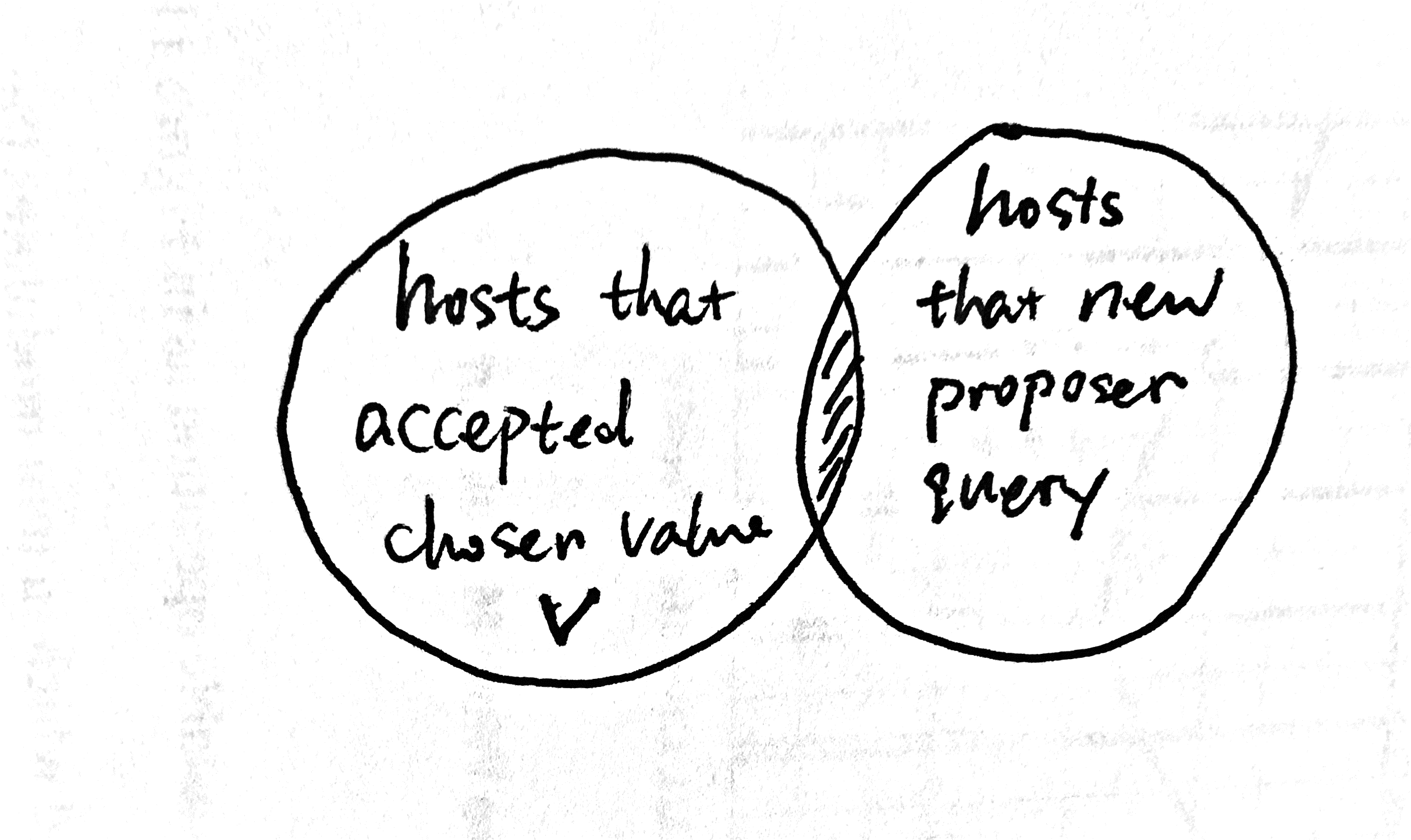

How do we know which value is chosen? We know, by definition, that if a value is chosen, it must be accepted by the majority Acceptors, in which case, if the Proposer reads from the majority Acceptors the chosen value must be in at least one of the responses. (This is exactly why we only need quorum of phase 1 and quorum of phase 2 to intersect for Paxos correctness. This is also called Flexible Paxos.)

How do we tell the chosen value v, from the rest of the accepted values? We can sort the accepted values by terms, in which they are accepted. We can come up with an algorithm so that,

Invariant(2): if a value X is chosen at term N, any proposal with term >= N must be with value X.

From invariant(2), it’s not hard to get that if a value is chosen, it must be the value of the proposal of the highest term from a quorum of Acceptors. Thanks to the intersection requirement, at least one of the Acceptors must have accepted the chosen value with term >= N (when the value is chosen). All proposals with term < N are not chosen and we don’t care about them. So if a value is chosen, a Proposer can find it out by just talking to a quorum of Acceptors.

Why invariant(2) holds for this algorithm? For any chosen value, there exists a term N that no value is chosen for terms <N. N is the first term when a value is chosen. If N = 1, the algorithm above is obviously correct. For N != 1, we don’t care about the proposal with term <N. Thanks again to the intersection requirement (between phase 1 and phase 2), we know at least one Acceptor must have accepted the chosen value at term N, and it’s the highest term at that moment. Following the algorithm, all future proposals with be proposing the chosen value, for terms >N.

Notice that neither the Proposer nor the Acceptor will know N (the first term when a value is chosen) for sure. It just makes it easier to prove the correctness of the algorithm.

Read-modify-write race

Like all read-modify-write cases, this can be racy. E.g. at the beginning, when no value is accepted, two Proposers can end up race with each other causing the second Proposer to overwrite the chosen value of the first one.

- p0 read accepted values (when nothing is accepted)

- p1 read accepted values (when nothing is accepted)

- p0 propose v0 and got accepted by majority (v0 chosen)

- p1 propose v1 and got accepted by majority (v1 chosen! This violates the Safety guarantee!)

A typical way to resolve a read-modify-write race is by putting an exclusive lock like 2pc, which won’t work in this case, as 2pc has its own fault-tolerance challenges. Another approach is to detect the race at write time and fail the write. We want the Acceptor to reject a proposal if the state has changed between the Proposer-read and the Proposer-write.

You guessed it, we can solve the race by leveraging our best friend, the fact that terms are globally totally ordered. Proposer can set the latest term on Acceptors on read, and Acceptor can use this latest_term to detect read-modify-write race.

This is exactly Paxos. It’s the same as the slide I showed at the top of this post.

Elegancy

Paxos is really elegant and concise because each state and phase serves multiple purposes.

A single term/ballot number is used for dual purposes

- find out potentially chosen value in phase one

- prevent read-modify-write race in phase two

Phase one serves the purpose of

- maintaining minProposalNumber to prevent read-modify-write race

- return accepted value with its proposal number, so a Proposer can change its proposal value to a potentially chosen one

Phase two serves the purpose of

- enforcing minProposalNumber to prevent read-modify-write race

- set accepted proposal, so it can be discovered by later Proposers

Liveness

Each Acceptor tracks the latest term it has seen, but for some term, there might not be an accepted value associated.

It’s possible that there are two Proposers, each talking to F disjoint hosts in the cluster and contending on the single overlapping host. In theory, it’s possible for these two Proposers to compete forever bumping the latest_term on the last Acceptor without letting it accept any value. In practice, the Proposer can select a somewhat random term id in the future, so that the probability of two Proposers contending forever on a single host is zero.

Summary

At a high level Paxos is a distributed read-modify-write transaction. Proposer first reads Acceptors to find out if there is a potential chosen value. If so, change the proposal to that value instead before propose the value to the Acceptors. It relies on the total order of terms/proposalIds/BallotNumber, to detect races that can happen in read-modify-write transactions.